Dr. Bryan G. Wallace

FARCE OF PHYSICS

Chapter 4

Publication Politics

Marilyn vos Savant is listed in the "Guinness Book of World

Records" under highest IQ and publishes an "Ask Marilyn" column

in the Sunday Newspaper Magazine PARADE. In the May 22, 1988

issue, Jennifer W. Webster of Slidell, La. asks:

What one discovery or event would prove all or most of modern

scientific theory wrong?

Marilyn replies:

Here's one of each. If the speed of light were discovered not

to be a constant, modern scientific theory would be

devastated. And if a divine creation could be proved to have

occurred, modern scientists would be devastated.

I suspect that Marilyn has hit the nail on the head. Einstein's

special relativity theory with his second postulate that the

speed of light in space is constant is the linchpin that holds

the whole range of modern physics theories together. Shatter

this postulate, and modern physics becomes an elaborate farce!

Along with the creation-science debate being published in the

letters section of Physics Today, there is also a continuing

debate on Einstein's relativity theories. My first entry[21]

into this debate was as follows:

Relativity debate continues

I would like to challenge two statements made by Allen D.

Allen (November, page 90) in his reply to Wallace Kantor on

the question of experimental relativity. Allen states "But

Kantor is incorrect in claiming that there is a reliable

experiment that refutes special relativity." With regard to

this statement the 1961 interplanetary radar contact with

Venus presented the first opportunity to overcome

technological limitations and perform direct experiments of

Einstein's second postulate of a constant light speed of c in

space. When the radar calculations were based on the

postulate, the observed-computed residuals ranged to over 3

milliseconds of the expected error of 10 microseconds from

the best fit the Lincoln Lab could generate, a variation

range of over 30,000%. An analysis of the data showed a

component that was relativistic in a c+v Galilean

sense.[18,19] With regards to Allen's statement "Einstein's

original contribution here was to assume that there just is

no ether, that is, no frame R such that one's speed with

respect to R affects the speed of light," Einstein and Infeld

state "This word ether has changed its meaning many times in

the development of science. At the moment it no longer

stands for a medium built up of particles. Its story, by no

means finished, is continued by the relativity theory."[20

p.153,21]

Part of my second letter[22] on this matter, goes as follows:

...Concerning Dehmer's comment "In choosing appropriate persons

to review the numerous manuscripts, the journal editors use

various methods that reflect their own style and areas of

expertise," I would like to present the following example of

how this has worked for me. On 3 June 1969, I submitted a

paper, "An Analysis of Inconsistencies in Published

Interplanetary Radar Data," to PRL. The last paragraph of the

referee report sent back August 15 states "It is suitable for

Physical Review Letters, if revised, and deserves immediate

publication if the radar data can be compared directly to

geocentric distances derived from optical directions and

celestial mechanics." I revised the paper as the referee

recommended and resubmitted it 21 August. The editor, S. A.

Goudsmit, sent me a reply 11 September, in which he stated that

the paper had been sent to another referee and rejected. I

sent a letter 13 September, complaining about the use of the

second referee. I received a reply from Goudsmit on 23

September, in which he then stated that he had made a mistake

in saying the paper had been sent to a second referee and that

it had actually been sent back to the first one. He did this,

in spite of the fact that there was absolutely no

correspondence between the two reports. They were obviously

typed on different typewriters, the first was completely

positive, while the second was strongly negative and made no

mention of the first report! I eventually published a revised

version "Radar Testing of the Relative Velocity of Light in

Space" in a less prestigious journal.[18] At the December 1974

AAS Dynamical Astronomy Meeting, E. M. Standish Jr of JPL

reported that significant unexplained systematic variations

existed in all the interplanetary data, and that they are

forced to use empirical correction factors that have no

theoretical foundation. In Galileo's time it was heresy to

claim there was evidence that the Earth went around the Sun, in

our time it is heresy to claim there is evidence that the speed

of light in space is not constant....

The above unfair treatment I received in trying to publish a

paper challenging Einstein's relativity theories, is not an

isolated incident. As an example, as I mentioned in Chapter 6,

in a June 1988 letter I received from Dr. Svetlana Tolchelnikova

from the USSR, she wrote that thanks to PERESTROIKA she was

writing me openly, but that her Pulkovo Observatory is one of the

outposts of orthodox relativity. Two scientists were dismissed

because they discovered some facts which contradicted Einstein.

It is not only dangerous to speak against Einstein, but which is

worse it is impossible to publish anything which might be

considered as contradiction to his theory. It seems the same

situation is true for her Academy. Lest one thinks that this

sort of repressive behavior with regard to relativity theory

happens only in the USSR, I have heard or read many horror

stories of this happening to scientists throughout the world. To

document the nature of the problem within the US, I would like to

make several quotes from a book on this problem by Ruggero M.

Santilli who is the director of The Institute for Basic Research:

This book is, in essence, a report on the rather extreme

hostility I have encountered in U.S. academic circles in the

conduction, organization and promotion of quantitative,

theoretical, mathematical, and experimental studies on the

apparent insufficiencies of Einstein's ideas in face of an

ever growing scientific knowledge.[23 p.7]

In 1977, I was visiting the Department of Physics at

Harvard University for the purpose of studying precisely non-

Galilean systems. My task was to attempt the generalization

of the analytic, algebraic and geometric methods of the

Galilean systems into forms suitable for the non-Galilean

ones.

The studies began under the best possible auspices. In

fact, I had a (signed) contract with one of the world's

leading editorial houses in physics, Springer-Verlag of

Heidelberg West Germany, to write a series of monographs in

the field that were later published in ref.s [24] and [25].

Furthermore, I was the recipient of a research contract with

the U.S. Department of Energy, contract number ER-78-S-02-

4720.A000, for the conduction of these studies.

Sidney Coleman, Shelly Glashow, Steven Weinberg, and other

senior physicists at Harvard opposed my studies to such a

point of preventing my drawing a salary from my own grant for

almost one academic year.

This prohibition to draw my salary from my grant was

perpetrated with full awareness of the fact that it would

have created hardship on my children and on my family. In

fact, I had communicated to them (in writing) that I had no

other income, and that I had two children in tender age and

my wife (then a graduate student in social work) to feed and

shelter. After almost one academic year of delaying my

salary authorization, when the case was just about to explode

in law suits, I finally received authorization to draw my

salary from my own grant as a member of the Department of

Mathematics of Harvard University.

But, Sidney Coleman, Shelly Glashow and Steven Weinberg and

possibly others had declared to the Department of Mathematics

that my studies "had no physical value." This created

predictable problems in the mathematics department which lead

to the subsequent, apparently intended, impossibility of

continuing my research at Harvard.

Even after my leaving Harvard, their claim of "no physical

value" of my studies persisted, affected a number of other

scientists, and finally rendered unavoidable the writing of

IL GRANDE GRIDO.*

* S. Glashow and S. Weinberg obtained the Nobel Prize in

physics in 1979 on theories, the so-called unified gauge

theories, that are crucially dependent on Einstein's special

relativity; subsequently, S. Weinberg left Harvard for The

University of Texas at Austin, while S. Coleman and S.

Glashow are still members of Harvard University to this

writing.[23 p.29]

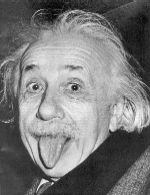

Even Albert Einstein was not immune from pressure from the

established politicians in the physics community with regard to

the sacred nature of the original special relativity theory,

especially with respect to the postulate of the constant speed of

light. For example the following quote is from a letter by Dr.

E. J. Post in a continuation of the relativity debate:

At the end of section 2 of his article on the foundations

of the general theory, Einstein writes: "The principle of

the constancy of the vacuum speed of light requires a

modification."[26] At the time, Max Abraham took Einstein to

task (in a rather unfriendly manner) about this deviation

from his earlier stance.[27]

With regard to the scientist's image of himself, Dr. Spencer

Weart writes:

A number of young scientists and science journalists,

mostly on the political left, declared that the proper way to

reshape society was to give a greater role to scientifically

trained peopleÄÄthat is, people like themselves.[17 p.31]

An excellent example of a physicist politician in action was

given by President Reagan's former national security adviser Dr.

John M. Poindexter who has a doctorate in nuclear physics from

the California Institute of Technology, in the 1987 US Senate

Iran-Contra hearings. Asked about his destruction of the

presidential order, known as a finding, that authorized the

November 1985 shipment of missiles to Iran and described it as an

arms-for-hostage swap, Poindexter denied that he did it to give

the President "deniability." "I simply did not want this

document to see the light of day," Poindexter said, puffing on

his pipe. Sen. Warren B. Rudman, the vice chairman of the Senate

panel, said Poindexter's stress on secrecy and deception was

"chilling." As a second example of the open arrogance and lack

of objectivity and integrity of the modern physicist politician,

I would like to quote from the published retirement address of

the particle physicist Dr. Robert R. Wilson, the 1985 president

of the American Physical Society:

Just suppose, even though it is probably a logical

impossibility, some smart aleck came up with a simple, self-

evident, closed theory of everything. IÄÄand so many

othersÄÄhave had a perfectly wonderful life pursuing the

will-o'-the-wisp of unification. I have dreamed of my

children, their children and their children's children all

having this same beautiful experience.

All that would end.

APS membership would drop precipitously. Fellow members,

could we afford this catastrophe? We must prepare a crisis-

management plan for this eventuality, however remote. First

we must voice a hearty denial. Then we should ostracize the

culprit and hold up for years any publication by the use of

our well-practiced referees.[28 p.30]

It might appear that Wilson was just trying to be funny, and that

his arguments do not have a remote possibility of being true. I

have learned over the years that many of the more prominent

politicians in physics love to clothe serious arguments with

humor. Wilson is well aware of the fact that APS editors go out

of their way to censor controversial material that could damage

the status and careers of the established politicians, such as

himself. To demonstrate Wilson's awareness and hypocrisy on this

question, I would like to quote from a letter I published in the

journal SCIENTIFIC ETHICS entitled SCIENTIFIC FREEDOM:

I attended the American Physical Society Council meeting at

the 1985 Spring APS meeting in Washington,D.C. The only real

debate that took place during the meeting was over the motion

to set up a million dollar contingency fund from the profits

derived from library subscriptions to the Physical Review

Journals. The point was that there was no real problem

raising large amounts of money. Toward the end of the

meeting, the President, Robert R. Wilson, expressed concern

over the problem of government censorship of publication and

presentation of papers at meetings.[29] The current increase

in censorship dealt mainly with various aspects of

lasers,[30] which apply to "Star Wars" research.[31] Wilson

proposed the idea that he could write letters to the

concerned government officials stating the APS Council's

resolution that "Affirms its support of unfettered

communication at the Society's sponsored meetings or in its

sponsored journals of all scientific ideas and knowledge that

are not classified."

I stated that it would be hypocrisy for him to send such a

letter since the Council does not practice what it preaches.

The Society's PR journals openly censor publication of papers

based on the philosophical prejudice of editors and anonymous

referees. Wilson dryly remarked that, "You have made your

point!"[32]

The point being that I had used the same argument in the

following letter published in Physics Today:

Scientific freedom

I would like to comment on Robert Marshak's editorial "The

peril of curbing scientific freedom" (January, page 192). At

an APS symposium in Washington, D.C., in 1982, our Executive

Secretary William Havens gave an invited paper whose

arguments were similar to those presented in Marshak's

editorial. In answer to my comments, which concerned the

inconsistency of his arguments in view of the fact that the

Physical Review journals used a policy of censorship similar

to that proposed by the government, Havens agreed with the

argument that there is no such thing as an objective

physicist, but defended the Physical Review policy on the

grounds that it saves paper and people are free to start

their own physics journal. I suspect that the government

officials concerned with creating the new censorship policy

who attended the symposium probably felt that national

security is a better reason for censorship than saving paper,

and, after all, anyone is free to move to a different

country.

The APS Council has approved a POPA resolution on open

communication (January,page 99). The resolution states that

the Council "Affirms its support of the unfettered

communication at the Society's sponsored meetings or in its

sponsored journals of all scientific ideas and knowledge that

are not classified." The policy of unfettered communication

at APS-sponsored meetings is an established practice, but it

has not been the policy of the APS Physical Review journals.

A Physical Review Letters editor has arbitrarily rejected a

current paper I submitted without sending it to a referee. I

suspect the true reason for the rejection was the fact that I

had the audacity to publish a letter in PHYSICS TODAY that

was critical of the journal's editorial policy (January 1983,

page 11). If the Council follows up on its resolution by

adopting a policy of allowing APS members the right to

publish in the Physical Review journals, the concerned

government officials will see that the resolution is more

than hypocritical rhetoric, and may see the wisdom of

adopting a similar policy![33]

Despite the hypocrisy, Wilson published an editorial titled "A

threat to scientific communication" in the July 1985 issue of

Physics Today that includes the following:

Membership in The American Physical Society is open to

scientists of all nations, and the benefits of Society

membership are available equally to all members. The

position of The American Physical Society is clear.

Submission of any material to APS for presentation or

publication makes it available for general dissemination. So

that there could be no doubt as to where our Society stands

on the question of open scientific communication, the Council

adopted a resolution on 20 November 1983 that concludes:

Be it therefore resolved that The American Physical

Society through its elected Council affirms its support

of the unfettered communication at the Society's

sponsored meetings or in its sponsored journals of all

scientific ideas and knowledge that are not

classified.[34]

A few months after the publication of my above "Scientific

freedom" letter that tended to show the APS Executive Secretary

in a bad light, the editor resigned! He was well known for his

editorials on just about every subject of interest to modern

physics, yet he wrote nothing about his intention to resign or

his long tenure as editor. The only mention of his resignation

was the following short notice:

Search committee established for Physics Today editor

At the end of 1984, the tenure of Harold L. Davis as editor

of PHYSICS TODAY came to an end. He has left the American

Institute of Physics to pursue other interests. AIP

director H. William Koch noted that during Davis's 15-year

stint as editor, PHYSICS TODAY became an important vehicle

for communication among physicists and astronomers and

reached a larger public as well. The magazine, he said, has

earned its reputation as authoritative, accurate and

responsive to the needs of the science community it

serves.[35]

Since then, I've been unable to publish any further letters in

Physics Today, no matter how important the subject. For example,

I made the startling discovery that the NASA Jet Propulsion

Laboratory was basing their analysis of signal transit time in

the solar system on Newtonian Galilean c+v, and not c as

predicted by Einstein's relativity theory. There is a short

mention of the major term in the equation as the "Newtonian light

time" but no emphasis on the enormous implications of this fact!

I tried to force this issue out into the open by submitting a

letter to Physics Today 9 July 1984, with the cover letter to the

editor indicating that I had sent a carbon copy to Moyer at JPL

for his comment on the matter. The following is the text of the

letter I submitted:

The speed of light is c+v

During a current literature search, I requested and

received a reprint of a paper[36] published by Theodore D.

Moyer of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. The paper reports

the methods used to obtain accurate values of range

observables for radio and radar signals in the solar system.

The paper's (A6) equation and the accompanying information

that calls for evaluating the position vectors at the signal

reception time is nearly equivalent to the Galilean c+v

equation (2) in my paper RADAR TESTING OF THE RELATIVE

VELOCITY OF LIGHT IN SPACE.[18] The additional terms in the

(A6) equation correct for the effects of the troposphere and

charged particles, as well as the general relativity effects

of gravity and velocity time dilation. The fact that the

radio astronomers have been reluctant to acknowledge the full

theoretical implications of their work is probably related to

the unfortunate things that tend to happen to physicists that

are rash enough to challenge Einstein's sacred second

postulate.[22] Over twenty-three years have gone by since the

original Venus radar experiments clearly showed that the

speed of light in space was not constant, and still the

average scientist is not aware of this fact! This

demonstrates why it is important for the APS to bring true

scientific freedom to the PR journal's editorial policy.[33]

I received a reply 4 January 1985, from Gloria B. Lubkin, the

Acting Editor following the Davis resignation, in which she said

they reviewed my letter to the editor and have decided against

publication. Since that time I've had two more rejections. On

14 January 1988 I submitted the following letter that contained

important published confirmation of my c+v analysis from a

Russian using analysis of double stars:

Relativity debate continues

In a letter in the August 1981 issue (page 11) I presented

the argument that my analysis of the published 1961 radar

contact with Venus data showed that the speed of light in

space was relativistic in the c+v Galilean sense. On 17

October 1987 I received a registered letter from Vladimir I.

Sekerin of the USSR. The translation of the letter by Drs.

William & Vivian Parsons of Eckerd College states:

"To me are known several of your works, including the work

on the radar location of Venus. Just as you do, I also

compute that the speed of light in a vacuum from a moving

source is equal to c+v.

I am sending you my article "Gnosiological Peculiarities in

the Interpretation of Observations (For example the

Observation of Double Stars)", in which is cited still one

more demonstration of this proposition. It is possible that

this work will be of interest to certain astrophysicists in

your country."

On 13 January 1988 I received a final translation of the

paper which was published in the Number IV 1987 issue of

CONTEMPORARY SCIENCE AND REGULARITY ITS DEVELOPMENT from

Robert S. Fritzius. The ABSTRACT states:

"de-Sitter failed disprove Ritz's C+V ballistic hypothesis

regarding the speed of light. C+V effects may explain

certain periodic intensity variations associated with visual

and spectroscopic double stars."

Since I realized that there was little chance that Physics Today

would publish the letter, after the passage of about 3 months, I

submitted a similar letter to the journal Sky & Telescope.

Within 2 days of mailing the letter, I received a reply from the

Associate Editor Dr. Richard Tresch Fienberg, in which he stated

that if a research result as unusual as this is being confirmed

by Soviet scientists, then the appropriate department of SKY &

TELESCOPE for the announcement is News Notes, not Letters.

Accordingly, he wanted me to send him copies of my original paper

and the English translation of the new Soviet work. I sent the

requested material, and within several weeks received a letter

from him saying that they have decided not to review my papers on

the relative velocity of light in their News Notes department at

this time. Dr. Fienberg was a co-author of a recent paper

published in the journal that states that their Big Bang

arguments are based on Einstein's general theory of

relativity![146]

Since Einstein's theories and his status as a scientist are at

the core of the problem of modern physics being an elaborate

farce, I will quote from various statements he has made with

regard to the issues that have been raised. In a June 1912

letter to Zangger he asked the question:

What do the colleagues say about giving up the principle of the

constancy of the velocity of light?[37 p.211]

With reference to the question of double stars presenting

evidence against his relativity theory, he wrote the Berlin

University Observatory astronomer Erwin Finlay-Freundlich the

following:

"I am very curious about the results of your research...," he

wrote to Freundlich in 1913. "If the speed of light is the

least bit affected by the speed of the light source, then my

whole theory of relativity and theory of gravity is false."

[38 p.207]

In a 1921 letter concerning a complex repetition of the

Michelson-Morley experiment by Dayton Miller of the Mount Wilson

Observatory, he wrote:

"I believe that I have really found the relationship between

gravitation and electricity, assuming that the Miller

experiments are based on a fundamental error," he said.

"Otherwise the whole relativity theory collapses like a house

of cards." Other scientists, to whom Miller announced his

results at a special meeting, lacked Einstein's qualifications.

"Not one of them thought for a moment of abandoning

relativity," Michael Polanyi has commented. "InsteadÄÄas Sir

Charles Darwin once described itÄÄthey sent Miller home to get

his results right."[38 p.400]

With regard to the question of scientific objectivity he states:

The belief in an external world independent of the

perceiving subject is the basis of all natural science. Since,

however, sense perception only gives information of this

external world or of "physical reality" indirectly, we can only

grasp the latter by speculative means. It follows from this

that our notions of physical reality can never be final. We

must always be ready to change these notionsÄÄthat is to say,

the axiomatic basis of physicsÄÄin order to do justice to

perceived facts in the most perfect way logically. Actually a

glance at the development of physics shows that it has

undergone far-reaching changes in the course of time.[39 p.266]

With respect to his own status he argues:

The cult of individuals is always, in my view, unjustified.

To be sure, nature distributes her gifts unevenly among her

children. But there are plenty of the well-endowed, thank God,

and I am firmly convinced that most of them live quiet,

unobtrusive lives. It strikes me as unfair, and even in bad

taste, to select a few of them for boundless admiration,

attributing superhuman powers of mind and character to them.

This has been my fate, and the contrast between the popular

estimate of my powers and achievements and the reality is

simply grotesque.[39 p.4]

In an expansion of this argument, he states:

My political ideal is democracy. Let every man be respected

as an individual and no man idolized. It is an irony of fate

that I myself have been the recipient of excessive admiration

and reverence from my fellow-beings, through no fault, and no

merit, of my own. The cause of this may well be the desire,

unattainable for many, to understand the few ideas to which I

have with my feeble powers attained through ceaseless struggle.

I am quite aware that it is necessary for the achievement of

the objective of an organization that one man should do the

thinking and directing and generally bear the responsibility.

But the led must not be coerced, they must be able to choose

their leader. An autocratic system of coercion, in my opinion,

soon degenerates. For force always attracts men of low

morality, and I believe it to be an invariable rule that

tyrants of genius are succeeded by scoundrels.[39 p.9]

On the question of scientific communication, he states:

For scientific endeavor is a natural whole, the parts of which

mutually support one another in a way which, to be sure, no one

can anticipate. However, the progress of science presupposes

the possibility of unrestricted communication of all results

and judgmentsÄÄfreedom of expression and instruction in all

realms of intellectual endeavor. By freedom I understand

social conditions of such a kind that the expression of

opinions and assertions about general and particular matters of

knowledge will not involve dangers or serious disadvantages for

him who expresses them. This freedom of communication is

indispensable for the development and extension of scientific

knowledge, a consideration of much practical import.[39 p.31]

With regard to Einstein's opinion on peer review of scientific

papers:

In the course of working on this last problem, Einstein

believed for some time that he had shown that the rigorous

relativistic field equations do not allow for the existence of

gravitational waves. After he found the mistake in the

argument, the final manuscript was prepared and sent to the

Physical Review. It was returned to him accompanied by a

lengthy referee report in which clarifications were requested.

Einstein was enraged and wrote to the editor that he objected

to his paper being shown to colleagues prior to publication.

The editor courteously replied that refereeing was a procedure

generally applied to all papers submitted to his journal,

adding that he regretted that Einstein may not have been aware

of this custom. Einstein sent the paper to the Journal of the

Franklin Institute and, apart from one brief note of rebuttal,

never published in the Physical Review again.[37 p.494]

On the question of peer review, I would like to make some

comments with regard to the article APS ESTABLISHES GUIDELINES

FOR PROFESSIONAL CONDUCT that was published in the journal

PHYSICS TODAY.[137] My first comment on the American Physical

Society guidelines concerns the fact that the C. Peer Review

section tends to contradict the intent of the guidelines on

ethics. In the second paragraph of the section we find the

sentence:

Peer review can serve its intended function only if the members

of the scientific community are prepared to provide thorough,

fair, and objective evaluations based on requisite expertise.

With reference to this point, as shown by my quotation of my

published letter,[33] the former APS Executive Secretary William

Havens agreed with the argument that there is no such thing as an

objective physicist, but defended the Physical Review policy on

the grounds that it saves paper and people are free to start

their own physics journal. I would like to point out the obvious

fact that if there is no such thing as an objective physicist, it

follows that there is no such thing as an objective peer review

of a physics paper! While it may be true that the APS Physical

Review policy saves paper for the journal, people are free to

start their own physics journals, and many of them have done so.

The result has created a crisis situation, not only for physics,

but for the rest of science as well. An illustration of this

problem is an article published in the New York Times newspaper

by William J. Broad titled Science publishers have created a

monster, the article was reprinted on page 1D of the February 20,

1988 edition of my local St. Petersburg Times newspaper. The

article starts:

The number of scientific articles and journals being

published around the world has grown so large that it is

starting to confuse researchers, overwhelm the quality-control

systems of science, encourage fraud and distort the

dissemination of important findings.

At least 40,000 scientific journals are estimated to roll

off presses around the world, flooding libraries and

laboratories with more than a million new articles each year.

An abstract of some statements taken from the rather large

article are as follows:

..."The modern scientist sometimes feels overwhelmed by the

size and growth rate of the technical literature," said Michael

J. Mahoney, a professor of education at the University of

California at Santa Barbara who has written about the journal

glut....Belver C. Griffith, a professor of library and

information science at Drexel University in Philadelphia, said:

"People had expected the exponential growth to slow down. The

rather startling thing is that it seems to keep rising...."But

experts say at least part of it is symptomatic of fundamental

ills, including the emergence of a publish-or-perish ethic

among researchers that encourages shoddy, repetitive, useless

or even fraudulent work....Surveys have shown that the majority

of scientific articles go virtually unread....It said useless

journals stocked by university libraries were adding to the

sky-rocketing cost of college education and proposed that

"periodicals go first" in a bout of "book burning."...An added

factor is that new technology is lowering age-old barriers to

science publication, said Katherine S. Chiang, chairman of the

science and technology section of the American Library

Association and a librarian at Cornell University....

Researchers know that having many articles on a bibliography

helps them win employment, promotions and federal grants. But

the publish-or-perish imperative gives rise to such practices

as undertaking trivial studies because they yield rapid

results, and needlessly reporting the same study in

installments, magnifying the apparent scientific output....In

some cases, authors pad their academic bibliographies by

submitting the same paper simultaneously to two or more

journals, getting multiple credit for the same work....A final

factor is the growth of research "factories," where large teams

of researchers churn out paper after paper....

An article titled Peer Review Under Fire states the following:

...Despite its crucial role in the era of "publish or perish,"

scientific peer review today limps along with its own disabling

wounds, asserts Domenic V. Cicchetti a psychologist with the

Veterans Administration Medical Center in West Haven, Conn. In

his comparative review of peer-review studies conducted over

the past 20 years by various researchers, Cicchetti finds

consistently low agreement among referees about the quality of

manuscript submissions and grant proposals in psychology,

sociology, medicine and physics....The belief that basic

research deserves generous funding because new understanding

springs from unexpected, serendipitous sources ÄÄ a cherished

argument in scientific circles ÄÄ implies that no one can

accurately forecast which work most needs financing and

publication, points out J. Barnard Gilmore, a psychologist at

the University of Toronto in Ontario....Gilmore envisions a

future in which journal and grant submissions reach a far-flung

jury of scientific peers through computerized electronic mail.

Rather than jostling for space in prestigious journals, authors

would vie for the attention of prestigious reviewers and other

readers who subscribe to the electronic peer network.

Reviewer's computerized suggestions and ratings would determine

a submission's funding or publication destiny....[138]

I believe that Gilmore's idea holds the key to the resolution of

the problem of scientific communication, except it would be far

more effective to have a hard copy paper journal that would be a

permanent archival record of the democratic debate of the far-

flung scientific peers. The computer far from being the cure, is

actually the major source of the problem. A word processing

program on a computer is a creative writing tool that makes it

possible to create a vast array of different very involved

abstract hard to understand articles using the same data base.

This business of acquiring status by publishing in a prestigious

journal after a peer-review is the core element of the problem.

If one acquired status by obtaining a large positive vote from

one's peers, one would try to write easy to understand

comprehensive articles with significant results and arguments,

thereby diminishing the size and cost of the scientific

literature.

My second comment is based on the following paragraph that

starts the D. Conflict of Interest section of the APS article:

There are many professional activities of physicists that have

the potential for a conflict of interest. Any professional

relationship or action that may result in a conflict of

interest must be fully disclosed. When objectivity and

effectiveness cannot be maintained, the activity should be

avoided or discontinued.

On page 1337 of a December 19, 1980 news article published in

SCIENCE you will find the following statements:

It was quite an admission, but there it was in a December

1979 editorial in the Physical Review Letters (PRL), the

favorite publishing place of American physicists: "...if two-

thirds of the papers we accept were replaced by two-thirds of

the papers we reject, the quality of the journal would not be

changed."...The fact that only 45 percent of the papers

submitted to PRL were accepted for publication helped the

journal gain an unintended measure of prestige. In the end,

the prestige associated with being published in PRL outweighed

the original criteria of timeliness and being of broad

interest....

Peer review is like communism, it sounds good in theory, but

because of human nature, does not work very well in actual

practice. If the APS Council is serious about scientific ethics,

they would eliminate the section on peer review, and do their

best to wean physicists away from this destructive practice in

the PR journals. Perhaps they could publish versions of the

journal where the authors would be completely responsible for the

content of their papers. The journal could reduce costs and

response time by having the authors submit camera ready

manuscripts that could be reduced to 1/4 size, and there would be

no reprints, but anyone, including the author, would have the

right to make as many copies as they wanted. I suspect that such

a journal would flourish, and even replace many of the so-called

prestigious journals. I would not be surprised to find its

format copied by many of the remaining journals, and that this

new trend would help resolve the current scientific communication

and ethics problems.

There seems to be a growing willingness of US newspapers to

print articles critical of relativity theory. For example, I

came across an article in the 3/10/91 edition of my local

newspaper that was reprinted from The New York Times. The title

of the article was Einstein's theory flawed? and the article

starts with:

A supercomputer at Cornell University, simulating a

tremendous gravitational collapse in the universe, has startled

and confounded astrophysicists by producing results that should

not be possible according to Einstein's general theory of

relativity....

In the body of the article Prof. Wheeler was mentioned as

follows:

Dr. John A. Wheeler, an emeritus professor of physics at

Princeton University and an originator of the concept of black

holes, said: "To me, the formation of a naked singularity is

equivalent to jumping across the Gulf of Mexico. I would be

willing to bet a million dollars that it can't be done. But I

can't prove that it can't be done."

In a 5/22/91 telephone call from Robert Fritzius, the man I

mentioned in Chapter 6, who accompanied me to the 1st Leningrad

Conference, he said that he had sent a reprint of his recently

published paper[142] to Prof. Wheeler, and that Wheeler had sent

back a very nice reply. The title of the paper was The Ritz-

Einstein Agreement to Disagree and mainly concerned the 1908 to

1909 battle between Ritz and Einstein that ended with a joint

paper.[143] In the 5. CONCLUSIONS Robert states:

...The current paradigm says that Einstein prevailed, but many

of us never heard of the battle, nor of Ritz's electrodynamics.

So if an earlier court gave the decision to Einstein, it did so

by default. Ritz, at age 31, died 7 July 1909, two months

after the joint paper was published.

An extremely interesting part of the paper was the 4. SECOND

THOUGHTS? section where Robert writes:

Einstein, in later years, may have had second thoughts about

irreversibility, but because of his revered position with

respect to the geometrodynamic paradigm was probably prevented

from expressing them publicly. We do have three glimpses into

his private leanings on the subject. In 1941 he called Wheeler

and Feynman's attention to Ritz's (1908) and Tetrode's (1921)

time asymmetric electrodynamic theories. [This was while

Wheeler and Feynman were laying the groundwork for their less

than successful (1945) time-symmetric absorber theory,[144]

which was really emission/absorber theory, with a lot of help

from the future. They could not embrace time asymmetry, but

Gill[145] now proposes to revitalize absorber theory by

creating a generalized version without advanced interactions.]

Two pieces of Einstein's private correspondence touch

indirectly on the subject of time asymmetry.[37 p.467] In

these letters Einstein expresses his growing doubts about the

validity of the field theory space continuum hypothesis and all

that goes with it.

To understand the nature of the problem you need to understand

20th century science as it really is, and not what it pretends to

be. An excellent article on this was published in Science by

Prof. Alan Lightman and Dr. Owen Gingerich. In the Discussion

section of the paper we find the following paragraph:

Science is a conservative activity, and scientist are

reluctant to change their explanatory frameworks. As discussed

by sociologist Bernard Barber, there are a variety of social

and cultural factors that lead to conservatism in science,

including commitment to particular physical concepts,

commitment to particular methodological conceptions,

professional standing, and investment in particular scientific

organizations.[147]

Dr. Chet Raymo, a physics professor at Stonehill College in

Massachusetts, and the author of a weekly science column in the

newspaper the Boston Globe, in a FOCAL POINT article published in

Sky & Telescope, expands on the above paper with the following

arguments:

Science has evolved an elaborate system of social

organization, communication, and peer review to ensure a high

degree of conformity with existing orthodoxy...

In a recent article titled "When Do Anomalies Begin?"

(Science, February 7th), Alan Lightman of MIT and Owen

Gingerich of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

describe the conservation of science. They acknowledge that

scientists may be reluctant to face change for the purely

psychological reason that the familiar is more comfortable than

the unfamiliar...

Usually, say Lightman and Gingerich, such anomalies are

recognized only in retrospect. Only when a new theory gives a

compelling explanation of previously unexplained facts does it

become "safe" to recognize anomalies for what they are. In the

meantime, scientists often simply ignore what doesn't fit...

For some people outside mainstream science, the path toward

truth seems frustratingly strewn with obstacles. Like everyone

else, scientists can be arrogant and closed-minded...[148]

The editor of the American Physical Society journal PHYSICS AND

SOCIETY, Prof. Art Hobson, wrote an editorial titled Redefining

Physics, and it starts as follows:

My friend Greg burst into my office the other day shaking

his head and asking "What are physicist good for, Hobson? Why

would anybody want to hire one? What is special about

physics?" He complained that PhD programs prepare graduates

who do things that only physicists care about, graduates who

settle into other departments where they prepare other students

to do the same thing. How can we change the barely self-

perpetuating system? Even relatively small reforms, such as

the Introductory University Physics Project's recommendations

for bringing introductory physics into the twentieth century

(let alone the twenty-first), are difficult. The system has

great inertia.

Greg is a successful quantum optics experimentalist. He

loves physics. He is one of our department's best teachers.

Despite having every reason to feel good about the future of

physics, he doesn't. He is not an isolated case. Judging from

recent surveys conducted by Leon Lederman and others, evidence

of low morale in the entire scientific community has been

building lately.

Within the body of the editorial, Prof. Hobson writes:

Congressman George Brown, Chair of the House science and

technology committee and one of science's best friends in

Congress, has recently written on these matters. Excerpts from

one of his articles are reprinted above. His strong words are

worthy of our attention.[149]

Some of the more interesting excerpts from one of Congressman

Brown's articles are as follows:

For the past 50 years, U.S. government support for basic

research has reflected a widespread but weakly held sentiment

that the pursuit of knowledge is a cultural activity

intrinsically worthy of public support...

...Lobbyists for the scientific community have been perhaps

excessively willing to bolster this rhetoric by claiming for

basic research an exaggerated role in economic growth...

...In fact, there are many tangible and intangible indicators

of a decline in the standard of living in the United States

today, despite 50 years of increasing government support for

research...

...In the absence of pluralistic democratic institutions,

science and technology can promote concentration of power and

wealth and even autocratic and dictatorial conditions of many

kinds. An excessive cultural reverence for the objective

lessons of science has the effect of stifling political

discourse, which is necessarily subjective and value-laden.

President Eisenhower recognized this danger when he stated that

"In holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we

should, we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger

that public policy could itself become the captive of a

scientific-technological elite."...

The fundamental challenge for all of us is not to increase

funding for research, it is to enhance the societal conditions

that permit research to thrive: educational and economic

opportunity, freedom of intellectual discourse, and an

increased capacity for all human beings to achieve their

individual potential within a just and humane global

society.[150]