Dr. Bryan G. Wallace

FARCE OF PHYSICS

Chapter 1

Sacred Science

The title of this book was inspired by Dr. Fritjof Capra's

book The Tao of Physics. Capra, a theoretical physicist states:

The purpose of this book is to explore this relationship

between the concepts of modern physics and the basic ideas in

the philosophical and religious traditions of the Far East.

We shall see how the two foundations of twentieth-century

physicsÄÄquantum theory and relativity theoryÄÄboth force us

to see the world very much in the way a Hindu, Buddhist, or

Taoist sees it, and how this similarity strengthens when we

look at the recent attempts to combine these two theories in

order to describe the phenomena of the submicroscopic world:

the properties and interactions of the subatomic particles of

which all matter is made. Here the parallels between modern

physics and Eastern mysticism are most striking, and we shall

often encounter statements where it is almost impossible to

say whether they have been made by physicists or Eastern

mystics. [1 p.4]

This presents an interesting question, what is the difference

between modern physics and Eastern mysticism? There was a

fascinating debate concerning creation-science published in the

letters section of the journal Physics Today that directly

relates to this question. The journal is sent free of charge to

all members of the American Physical Society. The Society is the

largest physics society in the world, and has world-wide

membership. The letters section is popular, and is probably the

most important communicative link between the world's physicists.

The following quote is from a letter by Prof. Harry W. Ellis, a

Professor of Physics at Eckerd College:

On the other hand, the scientist (or anyone) who dismisses

religion because the idea of an omnipotent God is logically

inconsistent is guilty of intellectual hypocrisy. Does he or

she think that science is free from inconsistencies? Perhaps

he or she is not aware of the existence of Russell's paradox

or Goedel's Theorem. Actually, aside from obvious

methodological differences, science and theology have much in

common. Each is an attempt to model reality, founded on

unprovable articles of faith. If the existence of a benign

supreme being is the fundamental assumption at the heart of

religion, certainly the practice of science is founded on the

unprovable hypothesis that the universe is rationalÄÄthat its

behavior is subject to human understanding. Through science

we construct highly useful models which permit us to

understand the universe, in the sense of predicting its

behavior. Let us not commit the elementary epistemological

mistake of confusing the model with reality. Surely

scientists, as well as religious leaders, should possess

sufficient maturity to realize that whatever ultimate reality

there may be is not directly accessible to mortal humans.[2]

Dr. Rodney B. Hall of the University of Iowa writes:

Perhaps faith or the lack of it is simply a matter of

indoctrination. You have been indoctrinated by the priests or

the professors or both.[3]

Dr. John C. Bortz of the University of Rochester argues:

Faith is not a valid cognitive procedure. When it is

accepted as such, the process of rational argumentation

degenerates into a contest of whims, and any idea, no matter

how absurd or evil, may be successfully defended by claiming

that those who advocate it feel, somehow, that it is right. In

such a philosophical environment ideas are accepted not on the

basis of how logical they are but rather on the basis of how

much "feeling" their advocates seem to have. Unfortunately,

the acceptance of ideas on this basis has been and continues to

be the dominant epistemological trend in the world.[4]

Dr. Anthony L. Peratt of Los Alamos states:

It is almost amusing to see the proponents of Big Bang

cosmology, who have themselves been accused of fostering a

religious intolerance toward those who question whether the

foundations of the Big Bang hypothesis are scientifically

justifiable, now getting a dose of their own medicine from

biblical creationists.[5]

Dr. Carl A. Zapffe presents the view that:

Science deserves every whack it gets from the so-called

creationists, for a charge of puritanical posture belongs as

much to one side as to the other.[6]

The governing body of the American Physical Society has

released the following official statement on the matter:

The Council of The American Physical Society opposes

proposals to require "equal time" for presentation in public

school science classes of the biblical story of creation and

the scientific theory of evolution. The issues raised by such

proposals, while mainly focused on evolution, have important

implications for the entire spectrum of scientific inquiry,

including geology, physics, and astronomy. In contrast to

"Creationism," the systematic application of scientific

principles has led to a current picture of life, of the nature

of our planet, and of the universe which, while incomplete, is

constantly being tested and refined by observation and

analysis. This ability to construct critical experiments,

whose results can require rejection of a theory, is fundamental

to the scientific method. While our society must constantly

guard against oversimplified or dogmatic descriptions of

science in the education process, we must also resist attempts

to interfere with the presentation of properly developed

scientific principles in establishing guidelines for classroom

instruction or in the development of scientific textbooks. We

therefore strongly oppose any requirement for parallel

treatment of scientific and non-scientific discussions in

science classes. Scientific inquiry and religious beliefs are

two distinct elements of the human experience. Attempts to

present them in the same context can only lead to

misunderstandings of both.[7]

I expect that the average scientist would agree with the

following argument presented by Dr. Michael A. Seeds:

...A pseudoscience is something that pretends to be a science

but does not obey the rules of good conduct common to all

sciences. Thus such subjects are false sciences.

True science is a method of studying nature. It is a set of

rules that prevents scientists from lying to each other or to

themselves. Hypotheses must be open to testing and must be

revised in the face of contradictory evidence. All evidence

must be considered and all alternative hypotheses must be

explored. The rules of good science are nothing more than the

rules of good thinkingÄÄthat is, the rules of intellectual

honesty.[8 p.A5]

This brings up an interesting question; Do scientists actually

practice what they preach? The evidence clearly shows that the

average scientist tends not to use the rules of good science. In

fact, it appears that Protestant ministers are inclined to have

more intellectual honesty than Ph.D. scientists. To document

this fact, I will quote from an article titled "Researchers Found

Reluctant to Test Theories" by Dr. David Dickson:

Despite the emphasis placed by philosophers of science on

the importance of "falsification"ÄÄthe idea that one of a

scientist's main concerns should be to try to find evidence

that disproves rather than supports a particular

hypothesisÄÄexperiments reported at the AAAS annual meeting

suggest that research workers are in practice reluctant to put

their pet theories to such a test.

In a paper on self-deception in science, Michael J. Mahoney

of the University of California at Santa Barbara described the

results of a field trial in which a group of 30 Ph.D.

scientists were given 10 minutes to find the rule used to

construct a sequence of three numbers, 2,4,6, by making up new

sequences, inquiring whether they obeyed the same rule, and

then announcing (or "publishing") what they concluded the rule

to be when they felt sufficiently confident.

The results obtained by the scientists were compared to

those achieved by a control group of 15 Protestant ministers.

Analysis showed that the ministers conducted two to three times

more experiments for every hypothesis that they put forward,

were more than three times slower in "publishing" their first

hypothesis, and were only about half as likely as the

scientists to return to a hypothesis that had already been

disconfirmed.[9]

There is an interesting article by Dr. T. Theocharis and Dr.

M. Psimopoulos of the Department of Physics of the Imperial

College of Science and Technology in London titled "Where science

has gone wrong," that explores the arguments put forth by

prominent scientists and philosophers with regard to the nature

of modern science.[10] The following is several quotes from that

article:

On 17 and 22 February 1986 BBC television broadcast, in the

highly regarded Horizon series, a film entitled "Science ...

Fiction?", and in the issue of 20 February 1986 The Listener

published an article entitled "The Fallacy of Scientific

Objectivity". As is evident from their titles, these were

attacks against objectivity, truth and science....

This state of affairs is bad enough. But things are even

worse: perversely, many individual scientists and philosophers

seem bent on questioning and rejecting the true theses, and

supporting the antitheses. For example, most of the

participants in the "Science ... Fiction?" film were academic

scientists....

Popper also thought that observations are theory-laden. He

phrased it thus: "Sense-data, untheoretical items of

observation, simply do not exist....[11]

But if observations are theory-laden, this means that

observations are simply theories, and then how can one theory

falsify (never mind verify) another theory?...[12]

So back to square one: if verifiability and falsifiability

are not the criteria, then what makes a proposition scientific?

It is hard to discern the answer to this question in Lakatos's

writings. But if any answer is discerned at all, it is one

that contradicts flagrantly the motto of the Royal Society: "I

am not bound to swear as any master dictates".[13] This answer

is more obvious in Thomas Kuhn's[14] writings: a proposition is

scientific if it is sanctioned by the scientific establishment.

(Example: if the scientific establishment decrees that "fairies

exist", then this would be scientific indeed.)

According to Kuhn, science is not the steady, cumulative

acquisition of knowledge that was portrayed in old-fashioned

textbooks. Rather, it is an endless succession of long

peaceful periods which are violently interrupted by brief

intellectual revolutions. During the peaceful period, which

Kuhn calls "normal science", scientists are guided by a set of

theories, standards and methods, which Kuhn collectively

designates as a "paradigm". (Others call it a "world-view".)

During a revolution, the old paradigm is violently overthrown

and replaced by a new one....

Kuhn's view, that a proposition is scientific if it is

sanctioned by the scientific establishment, gives rise to the

problematic question: what exactly makes an establishment

"scientific"? This particular Gordian knot was cut by Paul

Feyerabend: any proposition is scientificÄÄ"There is only one

principle that can be defended under all circumstances and in

all stages of human development. It is the principle: Anything

goes"....[15]

In 1979 Science published a four-page complimentary

feature[16] about Feyerabend, the Salvador Dali of academic

philosophy, and currently the worst enemy of science. In this

article Feyerabend was quoted as stating that "normal science

is a fairy tale" and that "equal time should be given to

competing avenues of knowledge such as astrology, acupuncture,

and witchcraft." Oddly, religion was omitted. For according

to Feyerabend (and the "Science ... Fiction?" film too),

religionÄÄand everything elseÄÄis an equally valid avenue of

knowledge. In fact on one occasion Feyerabend

characteristically put science on a par with "religion,

prostitution and so on."[15]

The above mentioned Prof. Thomas S. Kuhn, was a man who wrote a

controversial book on science. In an interview of Kuhn by John

Horgan on page 40 of the May 1991 issue of the prestigious US

journal SCIENTIFIC AMERICAN, we find the following:

... "The book" The Structure of Scientific Revolutions,

commonly called the most influential treatise ever written on

how science does (or does not) proceed. Since its publication

in 1962, it has sold nearly a million copies in 16 languages,

and it is still fundamental reading in courses on the history

and philosophy of science.

The book is notable for having spawned that trendy term

"paradigm." It also fomented the now trite idea that

personalities and politics play a large role in science.

Perhaps the book's most profound argument is less obvious:

scientists can never fully understand the "real world" or

evenÄÄto a crucial degreeÄÄone another...

Denying the view of science as a continual building process,

Kuhn asserts that a revolution is a destructive as well as a

creative event. The proposer of a new paradigm stands on the

shoulders of giants and then bashes them over the head. He or

she is often young or new to the field, that is, not fully

indoctrinated....

Dr. Spencer Weart directs the Center for History of Physics at

the American Institute of Physics in New York. In his

interesting article THE PHYSICIST AS MAD SCIENTIST published in

Physics Today, he writes:

The public image of the scientist partly evolved out of ideas

about wizards. Here was an impressive figure, known to all

from early childhood, reaching back through ancient sorcery

legends to prehistoric shamans.[17 p.28]

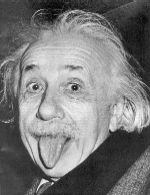

Prof. Albert Einstein states the following on the general lack

of scientific integrity in the temple of science:

In the temple of science are many mansions, and various

indeed are they that dwell therein and the motives that have

led them thither. Many take to science out of a joyful sense

of superior intellectual power; science is their own special

sport to which they look for vivid experience and the

satisfaction of ambition; many others are to be found in the

temple who have offered the products of their brains on this

altar for purely utilitarian purposes. Were an angel of the

Lord to come and drive all the people belonging to these two

categories out of the temple, the assemblage would be seriously

depleted, but there would still be some men, of both present

and past times, left inside.[39 p.224]

In Ronald W. Clark's definitive biography of Einstein, we find

what Einstein means when he makes the above statement pertaining

to the Lord, or some of his other famous statements such as "God

is subtle, but he is not malicious" or "God does not play dice

with the world.":

However Einstein's God was not the God of most other men.

When he wrote of religion, as he often did in middle and later

life, he tended to adopt the belief of Alice's Red Queen that

"words mean what you want them to mean," and to clothe with

different names what to more ordinary mortalsÄÄand to most

JewsÄÄlooked like a variant of simple agnosticism. Replying in

1929 to a cabled inquiry from Rabbi Goldstein of New York, he

said that he believed "in Spinoza's God who reveals himself in

the harmony of all that exists, not in a God who concerns

himself with the fate and actions of men." And it is claimed

that years later, asked by Ben-Gurion whether he believed in

God, "even he, with his great formula about energy and mass,

agreed that there must be something behind the energy." No

doubt. But much of Einstein's writing gives the impression of

belief in a God even more intangible and impersonal than a

celestial machine minder, running the universe with

undisputable authority and expert touch. Instead, Einstein's

God appears as the physical world itself, with its infinitely

marvelous structure operating at atomic level with the beauty

of a craftsman's wristwatch, and at stellar level with the

majesty of a massive cyclotron. This was belief enough. It

grew early and rooted deep. Only later was it dignified by the

title of cosmic religion, a phrase which gave plausible

respectability to the views of a man who did not believe in a

life after death and who felt that if virtue paid off in the

earthly one, then this was the result of cause and effect

rather than celestial reward. Einstein's God thus stood for an

orderly system obeying rules which could be discovered by those

who had the courage, the imagination, and the persistence to go

on searching for them. And it was to this task which he began

to turn his mind soon after the age of twelve. For the rest of

his life everything else was to seem almost trivial by

comparison.[38 p.38]

In an expansion of Einstein's views with regard to a scientific

cosmic religion, Clark states:

Maybe. To some extent the differences between Einstein and

more conventional believers were semantic, a point brought out

in his "Religion and Science" which, on Sunday, November 9,

occupied the entire first page of the New York Times Magazine.

"Everything that men do or think," it began, "concerns the

satisfaction of the needs they feel or the escape from pain."

Einstein then went on to outline three states of religious

development, starting with the religion of fear that moved

primitive people, and which in due course became the moral

religion whose driving force was social feelings. This in turn

could become the "cosmic religious sense ... which recognizes

neither dogmas nor God made in man's image." And he then put

the key to his ideas in two sentences. "I assert that the

cosmic religious experience is the strongest and noblest

driving force behind scientific research." And, as a

corollary, "the only deeply religious people of our largely

materialistic age are the earnest men of research."[38 p.516]

With reference to the general view of most scientists with

regard to science and religion, there is a very interesting FOCAL

POINT article in the journal Sky & Telescope by Dr. Paul Davies,

a professor of mathematical physics at the University of Adelaide

Australia.[139] The title of the article is What Hath COBE

Wrought?, and the following statements are from the article:

THE BLAZE of publicity that accompanied the recent discovery of

ripples in the heat radiation from the Big Bang focused

attention once again on the subject of God and creation.

Commentators disagree on the theological significance of what

NASA's Cosmic Background Explorer, or COBE, found. Some

referred to the ripples as the "fingerprint of God," while

others lashed out at what they saw as the scientists' attempt

to demystify God's last refuge.

When the Big Bang theory became popular in the 1950s, many

people used it to support the belief that the universe was

created by God at some specific moment in the past. And some

still regard the Big Bang as "the creation" ÄÄ a divine act to

be left beyond the scope of science.... Cosmologist regard the

Big Bang as marking the origin of space and time, as well as of

matter and energy.... This more sophisticated, but abstract,

idea of God adapts well to the scientific picture of a universe

subject to timeless eternal laws.... If time itself began with

the Big Bang, then the question "What caused the Big Bang?" is

rendered meaningless.... New and exciting theories of quantum

cosmology seek to explain the origin of the universe within the

framework of scientific law. Their central feature is

Heisenberg's uncertainty principle, which permits genuine

spontaneity in nature. As a result, the tight linkage between

cause and effect so characteristic of classical physics is

loosened. Quantum events do not need well-defined prior

causes; they can be regarded as spontaneous fluctuations. It

is then possible to imagine the universe coming into being from

nothing entirely spontaneously, without violating any laws.

Sir Isaac Newton, in his reasoning in support of the particle

(corpuscular) model of light in space, as opposed to the wave in

ether model, presented the argument:

Against filling the Heavens with fluid mediums, unless they be

exceeding rare, a great Objection arises from the regular and

very lasting motions of the Planets and Comets. For thence it

is manifest, that the Heavens are void of all sensible

resistance, and by consequence of all sensible matter.[140]

In 1846 Michael Faraday wrote in his diary:

All I can say is, that I do not perceive in any part of space,

whether (to use the common phrase) vacant or filled with

matter, anything but forces and the lines in which they

exerted.[141]

This was the beginning of the dominant modern physics theories,

where it is the geometric and physical conditions of space itself

that is fundamental. Prof. Eyvind H. Wichmann, in the Berkeley

Physics Course, Volume 4, quantum physics, presents the following

argument:

35 Today the mechanical ether has been banished from the

world of physics, and the word "ether" itself, because of its

"bad" connotations, no longer occurs in textbooks on physics.

We talk ostentatiously about the "vacuum" instead, thereby

indicating our lack of interest in the medium in which waves

propagate. We no longer ask what it is that "really

oscillates" when we study electromagnetic waves or de Broglie

waves. All we wish to do is to formulate wave equations for

these waves, through which we can predict experimentally

observable phenomena....[122]

There is a popular argument that the world's oldest profession

is sexual prostitution. I think that it is far more likely that

the oldest profession is scientific prostitution, and that it is

still alive and well, and thriving in the 20th century. I

suspect that long before sex had any commercial value, the

prehistoric shamans used their primitive knowledge to acquire

status, wealth, and political power, in much the same way as the

dominant scientific and religious politicians of our time do. So

in a sense, I tend to agree with Weart's argument that the

earliest scientists were the prehistoric shamans, and the

argument of Feyerabend that puts science on a par with religion

and prostitution. I also tend to agree with the argument of

Ellis that states that both science and theology have much in

common, and both attempt to model reality on arguments based on

unprovable articles of faith. Using the logic that if it looks

like a duck, quacks like a duck, and waddles like a duck, it must

be a duck: I support the argument that since there is no

significant difference between science and religion, science

should be considered a religion! I would also agree with Ellis'

argument of the obvious methodological differences between

science and the other religions. The other dominant religions

are static because their arguments are based on rigid doctrines

set forth by their founders, such as Buddha, Jesus, and Muhammad,

who have died long ago. Science on the other hand, is a dynamic

religion that was developed by many men over a long period of

time, and it has a flexible doctrine, the scientific method, that

demands that the arguments change to conform to the evolving

observational and experimental evidence.

The word science was derived from the Latin word scientia,

which means knowledge, so we see that the word, in essence, is

just another word for knowledge. An associate of mine, Prof.

Richard Rhodes II, a Professor of Physics at Eckerd College, once

told me that students in his graduate school used to joke that

Ph.D. stood for Piled higher and Deeper. If one considers the

vast array of abstract theoretical garbage that dominates modern

physics and astronomy, this appears to be an accurate description

of the degree. Considering the results from Mahoney's field

trial that showed Protestant ministers were two to three times

more likely to use scientific methodology than Ph.D. scientists,

it seems reasonable to consider that they have two to three times

more right to be called scientists then the so-called Ph.D.

scientists. I would agree with Popper's argument that

observations are theory-laden, and there is no way to prove an

argument beyond a reasonable shadow of a doubt, but at the very

least, the scientist should do more than pay lip service to the

scientific method. The true scientist must have faith and

believe in the scientific method of testing theories, and not in

the theories themselves. I agree with Seeds argument that "A

pseudoscience is something that pretends to be a science but does

not obey the rules of good conduct common to all sciences."

Because many of the dominant theories of our time do not follow

the rules of science, they should more properly be labeled

pseudoscience. The people who tend to believe more in theories

than in the scientific method of testing theories, and who ignore

the evidence against the theories they believe in, should be

considered pseudoscientists and not true scientists. To the

extent that the professed beliefs are based on the desire for

status, wealth , or political reasons, these people are

scientific prostitutes.

I agree with Newton's argument that if light was a wave in the

ether, the ether would have to be nonsensible matter. Calling

the ether space or vacuum does not solve the problem. Its

existence is based on blind faith and not experimental evidence.

As I will show in the following Chapters, there is an

overwhelming body of evidence that light is a particle, as Newton

predicted. The fact that most modern physicists have refused to

objectively consider this evidence, has made a farce of physics.

This empty space of modern physics is a supernatural solid[123]

that can have infinite temperature and density.[105] A spot of

this material that is smaller than an atom is supposed to have

created the entire universe.[8 p.325] This physical material has

become the God of most modern physicists!